Source: ALJAZEERA

ALJAZEERA MEDIA NETWORK

South Africa has legalized personal cannabis use, leading to discussions on whether other African countries will follow suit.

On the eve of the May 27 general elections, which saw the ruling African National Congress lose its majority for the first time in 30 years of South African democracy, a significant change to the country’s drug laws was made, barely noticed by most people.

Just one day before the historic vote, President Cyril Ramaphosa signed the Cannabis for Private Purposes Act, making South Africa the first African nation to legalize marijuana use.

The bill removes cannabis from the country’s list of banned narcotics, allowing adults to grow and use the plant (except in the presence of children). It also mandates that those previously convicted for such activities should have their records automatically expunged. However, the details of this process remain unclear, as does the fate of the 3,000 individuals imprisoned for cannabis-related offenses as of 2022.

After years of advocacy and negotiations, activists assert that the struggle is not yet over.

“[Ramaphosa] finally signed the law, and cannabis is no longer classified as a dangerous substance in South Africa,” Myrtle Clarke, co-founder of the cannabis reform NGO Fields of Green for ALL, told Al Jazeera from Johannesburg.

“Now we need to address the issue of trade, which remains illegal.”

Unlike other nations where cannabis has been legalized, like Malta, Canada, and Uruguay, South Africa currently offers no legal way to obtain it for casual use unless you grow it yourself. Selling cannabis remains unlawful unless prescribed for medicinal purposes by a doctor.

“The legislation ensures that if caught with an amount of cannabis deemed too large for personal use by the police, one cannot be charged as a dealer,” Clarke explained.

Effectively, it is permissible to cultivate cannabis privately as long as it is not sold for profit. However, a substantial grey market already exists.

The new law has been in development for six years. Following a 2018 court ruling that deemed private cannabis use constitutional, the government was instructed to draft legislation to legalize it within two years.

Since then, dispensaries and shops have been selling cannabis under Section 21 of the Medicines Act, which allows for “unregistered medicines” prescribed by a doctor. The 2018 ruling allowed cannabis to be included in this list.

“We don’t have any issues with the police,” the owner of a Durban dispensary told Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity.

“Only if you’re selling to minors or something other than weed, like magic mushrooms. Otherwise, some police even come here to smoke and protect us.”

However, some dispensaries and “private members’ clubs” operating under the “private consumption” principle have been targeted by authorities. The Haze Club (THC) in Johannesburg, for instance, was raided in 2020, and legal proceedings are still ongoing.

“These dispensaries are widespread across South Africa,” added Charl Henning, another member of Myrtle’s team.

With speculation about the legislation growing late last year, more dispensaries have sprung up.

“In the last six months, clubs and shops have proliferated, saturating the market, and now there’s no law to shut them down. Trade is already widespread; we just need to regulate it.”

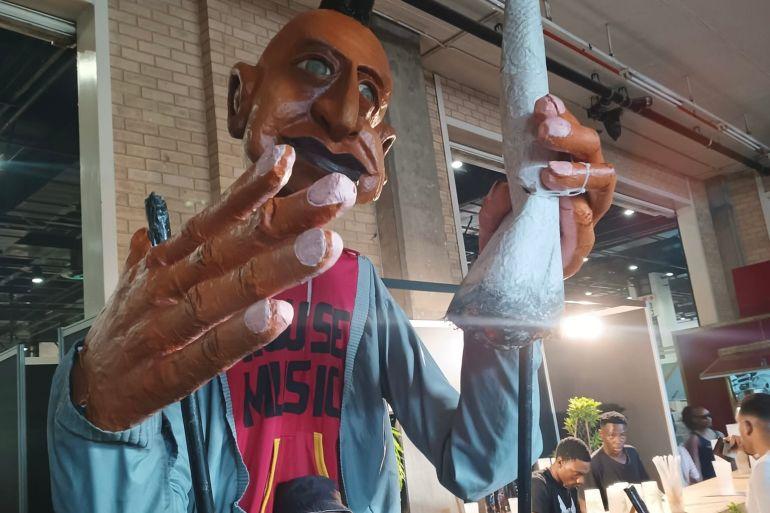

The 2022 Cannabis Expo in Johannesburg, South Africa.

The 2022 Cannabis Expo in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Southern Africa has one of the longest histories with cannabis, likely introduced to the continent by medieval Arab merchants. By the time Dutch settlers arrived in modern-day Cape Town in the mid-17th century, they found the native Khoisan people using the plant, which they called “dagga” (pronounced “da-kha”).

Cannabis had various uses: Zulu warriors smoked it to calm their nerves before battle, and it provided pain relief during childbirth for Sotho women. European settlers even began cultivating it to keep their non-white laborers “content,” though few indulged themselves.

While colonial authorities initially ignored native cannabis use, the introduction of Indian laborers in the 19th century brought new concerns. Believing ganja, the term for cannabis in South and Southeast Asia, made the laborers “lazy and insolent,” an 1870 law banned selling dagga to coolies.

Fears about dagga use grew as Black South Africans moved to urban centers in the early 20th century. Anxieties peaked when The Sunday Times in 1911 suggested that white workers were in danger of succumbing to the drug. Consequently, in 1922, South Africa imposed a nationwide ban on selling, growing, and possessing cannabis and called for its global prohibition.

During apartheid, the National Party's 1971 drug law was among the world’s strictest, with severe penalties felt most acutely in segregated townships. However, rural areas, particularly the Eastern Cape's “dagga belt,” were relatively left alone.

Post-apartheid, the 1992 Drugs and Drug Trafficking Act kept strict cannabis laws. Police often sprayed herbicides over dagga fields.

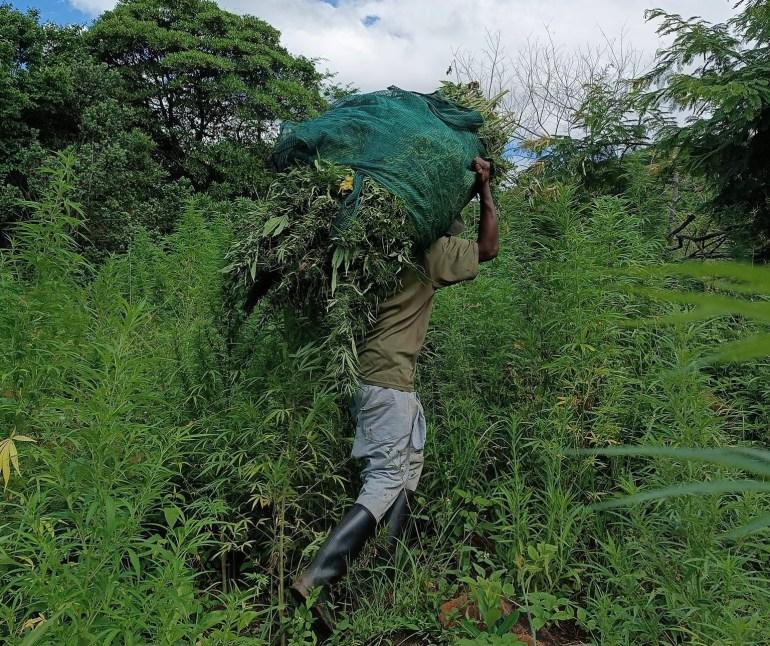

A man collecting and carrying cannabis leaves in the Hhohho region of Eswatini.

A man collecting and carrying cannabis leaves in the Hhohho region of Eswatini.

The so-called war on drugs persisted until 2017 when the Western Cape High Court ruled in favor of Rastafarian lawyer Ras Gareth Prince, who had been arrested for growing dagga. The court declared that the ban violated his privacy rights, a decision upheld by the Constitutional Court in 2018. Arrests dropped, and in 2023, the police officially stopped making “pot busts.”

The government was given two years to update its laws, but deadlines were repeatedly missed until the new law was finally enacted.

Myrtle considers it a start despite its imperfections. “We’ve had a tough fight with the [cannabis] community, with many finding the new law too flawed,” she said. “We decided to accept it with its flaws rather than face countless parliamentary meetings. We didn’t entirely win, but the bill’s publication allows progress.”

She now aims to regulate trade and overcome societal perceptions that cannabis is dangerous, accusing lawmakers of ignorance and prejudice.

Steve Rolles, a UK-based policy analyst, believes South Africa’s cautious approach might prevent a situation like Thailand’s, where rapid cannabis reforms led to a backlash.

Thailand removed cannabis from its Narcotics Act in 2022, leading to thousands of quasi-legal dispensaries. The swift changes caused public concern, leading lawmakers to reconsider the reforms.

“South Africa’s more measured approach, without commercial sales, suggests it won’t face the same challenges as Thailand,” Rolles noted.

“This is a first for Africa, so we must await its effectiveness,” Rolles commented.

While a few African nations like Malawi recognize medical marijuana and others like Ghana have decriminalized minor possession, South Africa is the first to allow recreational use.

Elsewhere, Morocco legalized cannabis for medical and industrial purposes in 2021. With a long history of smoking for relaxation, full legalization is now a topic of public debate, involving cannabis farmers, investors, and MPs.

Eswatini, a neighbor of South Africa and Mozambique, closely watches these developments. Cannabis is banned under a British colonial law, which the government is reconsidering.

For decades, smallholder farmers in Eswatini have relied on illegally exporting insangu, including the prized Swazi Gold. However, South Africa’s changes may threaten their livelihoods.

“Legalizing cannabis in South Africa has led to unequal economic participation, risking the loss of our traditional cultivation practices and indigenous genetics,” stated Trevor Shongwe of the Eswatini Hemp and Cannabis Association.

Despite remaining underground in South Africa, lifting home cultivation restrictions has enabled growers to produce potent strains, competing with Swazi produce.

“For many rural people, cannabis is the main cash crop, providing a means of survival in impoverished Eswatini.”

Shongwe advocates for Eswatini to legalize its domestic market and trademark its Swazi Gold strain, akin to Mexico’s tequila and mezcal protections.

“Currently, there are no legal avenues for production. Local farmers can only thrive economically if cannabis is legalized and reforms empower them.”

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *