Source: ALJAZEERA

ALJAZEERA MEDIA NETWORK

A luxury residential complex in Dhaka highlights Bangladesh's economic disparities as wealth accumulates among a select few, raising issues of inequality and tax evasion.

Dhaka, Bangladesh: Adjacent to the exclusive Gulshan Club and overlooking the tranquil Gulshan Lake in Dhaka, a 14-storey structure is nearing completion.

Construction workers in orange helmets and bright harness belts are putting the final touches on the building’s elaborate facade, which contrasts starkly with its concrete and glass core.

This edifice, called Three, is being developed by the prestigious Bangladeshi real estate firm BTI and is considered the most costly residential building ever in the South Asian country.

The 12 apartments, each taking up an entire floor of over 7,000 square feet (650 square meters), are fitted with cutting-edge amenities, including biometric lock systems and elevators with AI-based lighting for energy efficiency.

All units were sold before the construction even started, despite the steep base price of 200 million taka or $2.5 million until 2021 (recent devaluation of the taka brought the price down to $1.8 million).

Since BTI chairman Faizur Rahman Khan also bought an apartment, the company carefully vetted other prospective owners from over 50 applicants, mostly city businessmen.

Signs of Bangladesh’s increasing disposable income are evident. Shopping centers like Jamuna Future Park, among the largest in South Asia, and billboards advertising a variety of products are testament to this growth.

Yet, this BTI structure epitomizes the burgeoning wealth among a small fraction of Bangladesh’s 180 million citizens.

A Boston Consulting Group (BCG) study emphasized the rapid growth of Bangladesh's middle-income and affluent consumer (MAC) class, predicted to reach 17 percent of the population by 2025, alongside a deepening wealth inequality.

The nation’s shift from being labelled an “economic basket case” by former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to a swiftly growing economy has underscored this divide.

Currently, the richest 10 percent in Bangladesh hold a disproportionate 41 percent of the country's total income, while the poorest 10 percent only receive 1.31 percent, according to government statistics.

Entrance of Three, the most expensive residential complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Entrance of Three, the most expensive residential complex in Dhaka, Bangladesh

A New York-based research firm, Wealth-X, identified Bangladesh as leading global wealth growth from 2010 to 2019.

The study (PDF) highlighted an impressive 14.3 percent annual increase in individuals with over $5 million in net worth, surpassing Vietnam’s 13.2 percent growth rate.

Wealth-X’s forecast also places Bangladesh among the top five fastest-growing regions for high-net-worth individuals, predicting an 11.4 percent growth over the next five years.

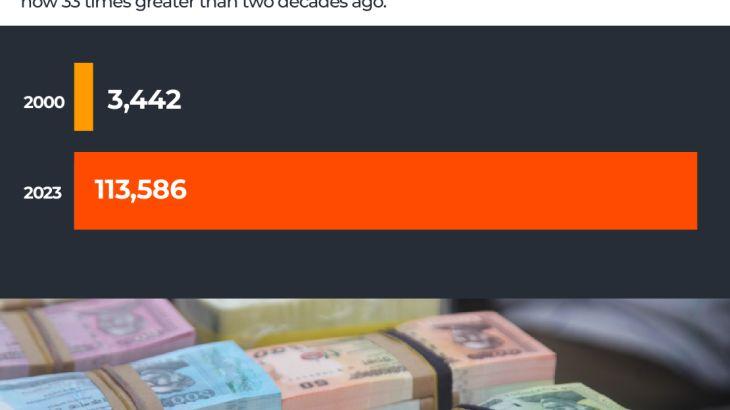

According to Bangladesh Bank, by the end of 2023, more than 113,586 private bank accounts held at least 10 million taka (nearly $1 million), a significant rise from just 16 accounts post-independence in 1971 and 3,442 accounts in 2000, marking the start of the country’s manufacturing and export surge.

This wealthy group, referred to as kotipotis, though less than 1 percent of total bank accounts, control 43.35 percent of total deposits, showing a stark concentration of wealth.

Economist MM Akash remarked, “Bangladeshi affluent individuals are amassing wealth while the impoverished are barely surviving.”

The disparity is glaring. Less than three kilometers from the Three building, alongside the same Gulshan Lake, lies Korail, Dhaka’s largest slum, starkly contrasting its affluent neighbor with four to five people cramped into tiny rooms.

Recent years have seen worsening poverty due to COVID, the Ukraine-Russia war, and economic slowdowns.

Various surveys report an increasing number of Bangladeshis falling into poverty. A BIDA survey indicated that 51 percent of Dhaka’s poor plunged into extreme poverty due to the pandemic.

Akash cited unequal economic gain distribution and development strategies favoring the ultra-rich as reasons for this widening gap.

Bangladesh's Eighth Five-Year Plan admits policy shortcomings in addressing persistent inequality and fair wealth distribution.

Akash pointed out that Bangladesh's 9 percent tax-to-GDP ratio is below the 15 percent average of other developing countries.

He criticized the regressive direct taxation on the poor and middle class, while the rich evade taxes, leaving massive portions of their assets untouched.

Khondaker Golam Moazzem of CPD criticized governments for prioritizing corporate tax cuts over taxing the wealthy.

“Workers face suppression for demanding fair wages, while the ultra-rich enjoy benefits even after tax evasion,” Moazzem noted.

A Ministry of Finance study indicated that 45-65 percent of Bangladesh’s income goes untaxed, due to the superrich undervaluing their assets to evade taxes.

Consequently, government revenue primarily comes from indirect taxes like VAT, burdening the poor excessively.

Moazzem stated that the poor bear a heavier tax load, rejecting the supply-side theory that breaks for the rich benefit everyone.

Economist Akash also challenged the portrayal of a thriving economy based on rising affluent numbers, arguing most rich people evade taxes by stowing their wealth in offshore accounts.

Interactive_Bangaldesh_Wealth3_account with 10million taka-1717786083

Interactive_Bangaldesh_Wealth3_account with 10million taka-1717786083

Oxfam’s 2023 Annual Inequality Report highlighted that the richest 1 percent globally amassed nearly twice as much wealth as the rest of the world over the last two years.

Billionaires’ wealth increased significantly since 2020, with the uber-rich gaining $26 trillion (63 percent) of all new wealth during the pandemic and living-cost crisis, while the remaining 99 percent shared $16 trillion (37 percent).

This results in a billionaire earning around $1.7 million for every $1 made by someone in the bottom 90 percent, with their wealth growing by $2.7 billion daily, widening the wealth gap.

Despite being the 35th largest economy globally, Bangladesh only saw its first billionaire on Forbes’ annual list this year—Muhammad Aziz Khan, chairman of Summit Group, who made his wealth from electricity and energy.

To illustrate, Eswatini, with a GDP 100 times smaller than Bangladesh’s, has had one billionaire.

Of the 76 countries with billionaires, 40 have smaller economies than Bangladesh’s.

Chile, with an economy 78 percent the size of Bangladesh’s, has seven billionaires. Similarly, Cyprus, with an economy one-15th of Bangladesh’s size, has four billionaires.

Journalist Sheikh Rafi Ahmed reported on these “missing billionaires,” arguing many exist in Bangladesh but keep their wealth abroad in offshore accounts, pointing to the 11 Bangladeshis named in the Pandora Papers for such practices. Rafi suggested that substantial capital outflow and tax evasion obscure the true wealth of individuals in Bangladesh.

“This likely explains the absence of Bangladeshi billionaires on global lists for long,” he theorized.

Naznin Ahmed of BIDS highlighted the severe rate of capital outflow through false invoicing of imports and exports.

A 2017 Global Financial Integrity Report ranked Bangladesh highest among least developed countries for “illicit financial flows,” due to the wealthy moving their money abroad.

“Bangladesh has secret billionaires, but their money isn’t kept here,” she concluded.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *